Mao

Zedong’s face has long graced trinkets and kitsch sold at tourist markets

across China. But in the country’s top art museums, his most famous portrayal

by a Westerner isn’t welcome.

Sorry,

Andy Warhol.

Although

the scion of Pop Art passed away in 1987, Warhol is still generating

controversy. A vast traveling retrospective of his work, “Andy Warhol: 15

Minutes Eternal,” has already made stops in Singapore and Hong Kong as part of

a two-year Asia tour, but when it moves to mainland China next month, the

artist’s Mao paintings won’t be coming along.

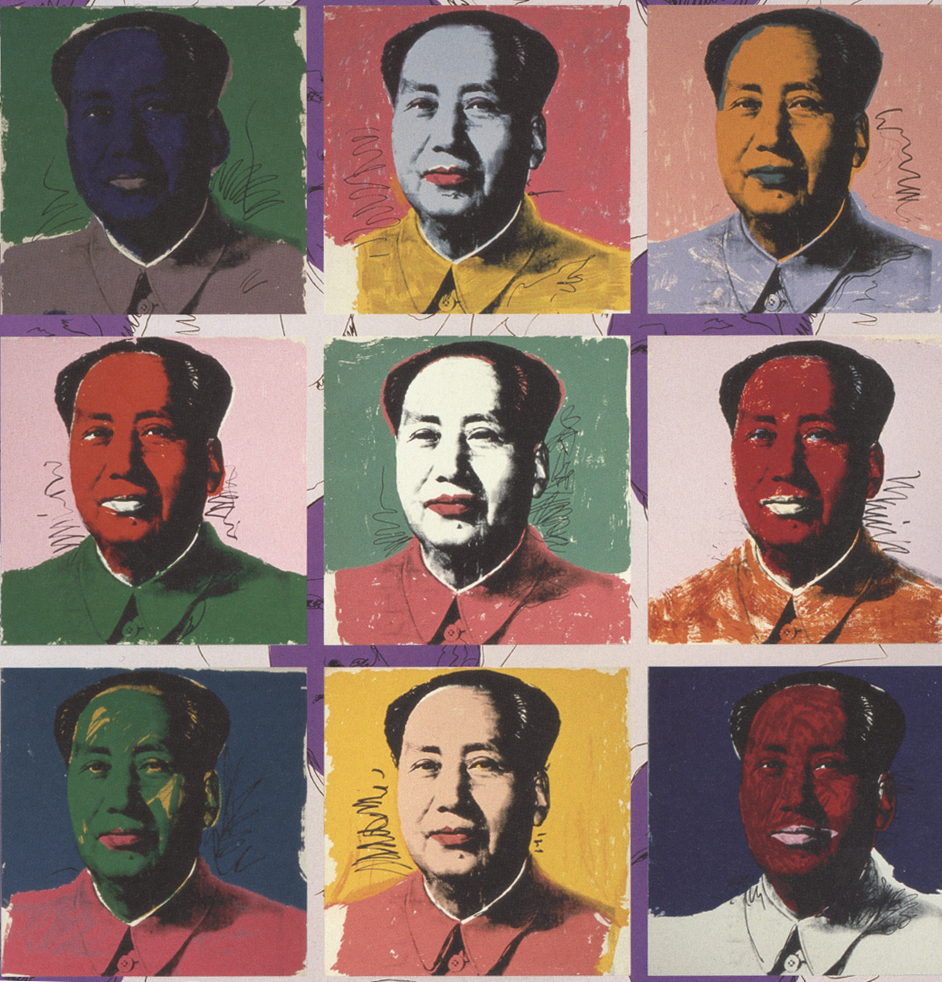

Organized

by the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the full exhibition consists of

hundreds of Warhol’s best-known artworks, including eight silkscreen paintings

of Mao. The museum declined to state where the Mao paintings would be kept

while the show is on display in Shanghai and Beijing, its two China stops.

“We

had hoped to include our Mao paintings in the exhibition to show Warhol’s keen

interest in Chinese culture,” said Andy Warhol Museum director Eric Shiner in a

statement. He added, “We understand that certain imagery is still not able to

be shown in China and we respect our host institutions’ decisions.”

The

museum’s staff declined to confirm the exhibition’s dates and venues for Shanghai

and Beijing. Its website currently says “check back for details” on the show

for both cities.

Nonetheless,

over the weekend Shanghai’s Power Station of Art, China’s first state-owned

gallery dedicated to contemporary art, posted on its website that it would host

“15 Minutes Eternal” from April 29 to July 28 with free entry. The Shanghai

institution did not reply to requests for comment.

In

an op-ed last month, the English-language edition of the state-owned Global

Times tabloid said that Warhol’s Mao paintings pushed the boundaries of

cultural acceptability. According to the author, color painted or splotched on

Mao’s face could appear like cosmetics — a disrespectful treatment of the

Chairman’s face.

Art

and controversy are common bedfellows in China. Pop Art was a major influence

for China’s contemporary artists in the 1980s and ’90s, among them Ai Weiwei,

whose persistent documentation of everyday life once earned him the nickname

“the Chinese Andy Warhol.” The artist’s detention by Chinese authorities in

April 2011 prevented him from visiting the Warhol Museum one month later.

In

the Hong Kong edition of “15 Minutes Eternal,” on view through April 1, the

public appeared to respond well to the Mao paintings, which were displayed with

a Mao print from the museum’s permanent collection.