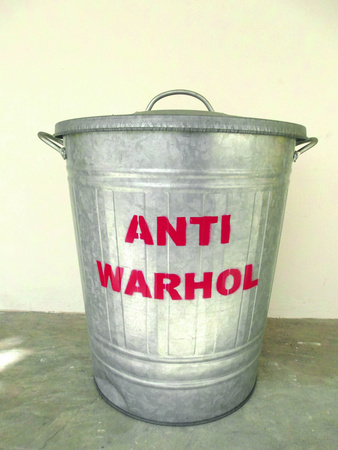

SINGAPORE - One of the first things you'll notice in Justin

Lee's Ten Years Of Art And Craft exhibition at Art Seasons gallery is a shiny

metal bin with the words "Anti Warhol" in stark red lettering.

Like Andy Warhol, Lee's career is backgrounded in graphic

design and commercial screenprinting. His mash-ups of eastern and western

cultural icons earned him the tag as a leading pop artist on our shores. So why

"Anti Warhol"?

For the Singaporean artist, even a well-meant label carries

with it the baggage of the past (although he would prefer to look at the

"now"). And besides, it's not as if Lee is all about pop art. He has

also been dabbling in performance art, a recent example being Eat Fast Food

Fast, at the Singapore Art Museum. In this video of the performance, we find

out that even though you can blend fast food, chugging down the resultant goo

probably isn't the most pleasant experience in the world - a rawness (though

tinged with humour) which might surprise those more familiar with his

intricate, polished prints, or his gleaming renditions of terracotta warriors.

Which is why focusing on the present is a good place to

start viewing Lee's eighth solo. Despite its title, it's not a survey of his

past decade of work. Rather, we've got Lee drawing on past memories and

influences to focus on the present, and the future.

Having lived and worked through the '80s and '90s, Lee has

trained his eyes on many of the rapid changes that have made Singapore the

massively globalised, networked city it is today. In a sense, you could say

that his pin-sharp, culture-remixing wit is just the foil to the lightning-fast

modernisation (some might say Westernisation) of Singapore.

The Lion City's story isn't just one of becoming a big shiny

city, though, and the show reflects that. It's particularly evident in his Singapore

Day series, one of which features in white a panoramic silhouette of our

skyline, with a vast red sky above. It is somehow quiet and turbulent at the

same time.

The show also features evolutions of previous themes, such

as a trio of paintings which seem to link the billowy-sleeved courtiers of old

China with China's first woman in space, via the unlikely figure of the late

Princess Diana.

That preoccupation with space travellers extends to Everyone

Loves Everyone, which seems twee at first (it's tiny spacemen on children's

rides) but carries an uncanny edge - the spacemen's blank, dripping faceplates

amplify the self-circularity of the title.

There are also significant departures and new directions,

but let's not spoil the surprises that Lee has in store.