Art history is, of course, full of referencing, echoing, quoting, and flat out copying. From the Renaissance artists who fished symbols and stories from a community pool to pop artists who fished in a pool of brand recognition, and onward to the appropriation artists we know today, who lift images from one work and place them in their own. Mimicry has become, by now, so ubiquitous that it would be hard to say who is, or is not, doing it. Derivative use ranges from very subtle (the moody "stills" of Cindy Sherman echoing Alfred Hitchcock's movies) to deliberately heavy-handed (the lurid often near re-staging of Sherman's works rendered by Alex Prager) and onward, to unapologetic piracy (the tracing and stencils of street artists).

So what dictates proper or improper use of someone else's art?

As I have mentioned before, the question seems to call up issues that move in and out of three categories: ethics, aesthetics, and law.

Appropriation Ethics: Who's Getting Paid for Who's Work

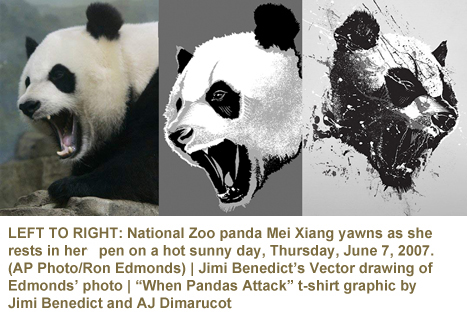

A former art director at OgilvyOne (a subdivision of Ogilvy & Mather) AJ Dimarucot used to design websites for O&M clients. But, in 2007, prompted by the desire to fund his upcoming wedding, he started freelancing on the side. After a few months, Dimarucot realized that his freelance dollars added up to more than his full-time pay. And since he was working for US-based clients, the dollar exchange was in his favor. So, in January 2008 he left OgilvyOne in order to focus on a freelance career:

"That's when I started to design more t-shirts and joined t-shirt contests. To me, the t-shirt had a finality that websites didn't have. It was 'finished' once it was printed. Whereas websites were a never ending twist of updates, revamps, changes, etc., and I got burnt out as an artist. The t-shirt became my canvas to express my art freely. So if I didn't get married, I wouldn't have started freelancing and discovered that side of my creativity."

Often we think about copyright as a way of owning, keeping, and selling ideas. This is why, when Gavin Brown says, ""I don't believe in the ownership of ideas or creativity," we scratch our heads and wonder why such a notion would cause any upset. It sounds lovely, communal, and has the added attraction of sounding radical.

But when you examine the investment that individuals like AJ Dimarucot put into their work, you become less likely to think of the products of their labor as "ideas" or "creativity," in the abstract, and more likely to recognize them as something concrete: they are created objects.

Lisa Shaftel, National Advocacy Committee Chair of the Graphic Artists Guild argues, "Copyright does not protect ideas. Copyright protects original works 'fixed in a tangible medium.'"

The way Lisa Shaftel sees it, "We are all free to think and to exchange ideas. However, we don't have the freedom to steal work from the people who produce it."

The ethical issue is just this, in a nutshell: If you take my artwork and sell it, you get paid for my artwork and everything I put into it, including my time and my effort.

This hurts all the more, Dimarucot explains:

"If [Pruitt] sells the panda painting for the [rumored] $95,000, I'd feel bad because I try to support a family with my art and this is a slap in the face. My art sells for peanuts compared to what he sells his art for. Threadless would probably have to sell a million t-shirts for me to get anywhere close to that amount."

In brief, Pruitt is getting paid thousands of dollars more for Dimarucot's work than Dimarucot is.

Meantime, Dimarucot's co-designer, Jimi Benedict, who has voiced nothing but extreme apathy thus far, feels quite differently:

"I already got paid and will continue to get paid for the design, provided it sells. Ain't no skin off my back if homes wants to try to profit off the painting he created. It probably helps to gain the shirt a little more publicity from all the brouhaha. Art is the business of hype, and a little bit of skill... mostly hype."

Appropriation Aesthetics

"I'm ok with appropriation," says Dimarucot, "as long as it builds upon the original context of the piece being appropriated (e.g. Warhol's soup cans). In Rob's case, I just don't see anything new with his work.

Immediately after the Threadless/Pruitt Panda story broke (as it were) the direction that criticism took was about whether or not Pruitt made the right creative decision in using the Threadless t-shirt graphic. In using a graphic that had no amassed cultural meaning, it was thought that perhaps he brought nothing in the line of social commentary or insight to the work. Was it an impoverished choice?

Said Paddy Johnson of ArtFagCity, "Appropriation without credit tends to be a little more morally acceptable when it moves upward not just because of class norms, but for the recognizability of those images."

Johnson's speculation echoes the thought of Jake Nickell, Founder and CSO for Threadless who says:

"I personally appreciate pop art that appropriates work from well known sources but don't think that [When Pandas Attack] is nearly ubiquitous enough to be used in that form. When you take something obscure and pass it off as your own, I don't think that's a very respectable or interesting thing to do."

In Pruitt's defense, though, he wasn't doing anything that he hadn't done before; and no one in the past had any beef with all those other cribbed pandas. Art critic, Michelle Grabner, says, "Pruitt acts as a conduit, shuffling images from mass culture to high art production." One could argue that Pruitt has made a successful career out of generic pop collage. If this was never an issue before, it really needn't be one now.

Indeed, in a separate blog entry Paddy Johnson expressed ambivalence: "Knowing the artists and fields is essential to understanding the dispute: Pruitt's been making panda bear paintings for ten years and freely appropriates found imagery. As Randy Kennedy of the New York Times notes in an email response to Gangnath, a member of the popular t-shirt forum emptees, 'this strategy has a long history in the art world.'"

True dat: after all, Jeff Koon's entire Banality series was comprised of grotesque echoes of vaguely familiar themes taken from all over the kitschosphere. He used obscure photographs to model his sculptures String of Puppies and Ushering in Banality -- and he was sued and lost the cases -- but the art itself was never criticized for failing to call up lofty or resounding references. One could argue, in fact, that points about banality or pop-culture-as-grab bag (in Pruitt's case) are better made through the use of obscure, but representative, images.

It is important to point out that, although Pruitt's panda painting struck many of us as a first, for dipping into un-branded culture, it has actually been the norm for a while. Warhol was sued for his flower paintings way back when, by a relatively unknown photographer. And we all know that Shepard Fairey uses the whole world as if it were a rainy day scissor project. Appropriation has, if you think about it, not been about reference for quite a while. It's more about echoes and sentiments and those are best ladled from the zeitgeist.