Andy Warhol’s Pop Riot

“The sophisticated audience that

had turned out to put down the art that was not on display provided a chilling

touch of surrealism worthy of Buñuel or Fellini”

by DAVID BOURDON

JUNE 16, 2020

The latest Arthurian exploit of

the legendary Andy Warhol occurred last Friday at the public opening of his

first comprehensive exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art on the

University of Pennsylvania campus. (The show closes on November 21.) At the

preview opening the night before, attended by 1600, a tuna fish painting was

impaled by a television light stand and Institute Director Samuel Adams Green

was himself pushed to the wall against a painting. Realizing he was up against

something big, Green took the unprecedented step of removing the paintings for

the public opening. Left up in three spacious rooms were a few dozen flower

paintings on one wall and about seven grocery carton sculptures in a corner.

Confronted by vistas of stark

white walls, the milling crowd, mostly students, debated the merits of the absent

art. TV reporters with mobile cameras interviewed earnest co-eds who pointed at

nail-studded walls and made pronouncements like: “I always thought art was supposed

to be creative,” “pop art is just comedy in art,” “all of his art is trash, you

know it, it’s got to be a fad.” The sophisticated audience that had turned out

to put down the art that was not on display provided a chilling touch of

surrealism worthy of Buñuel or Fellini.

By 10 p.m., one hour after

opening, 1000 people had crammed into the galleries and refused to budge. On

the wall opposite the flowers, a single crutch hung on a nail where a painting

had been, presumably left behind by someone now borne along by the crowd.

Andy and the Satellites were

recognized by their golden and silvered locks and engulfed in a sickening

crush. Forming a human chain, they sought refuge in the back room. Nearly

trampled in the melee was the entire pop art brain trust — Rosalind Constable,

Henry Geldzahler, and G. R. Swenson, all of them old hands at non-violent

museum openings.

The crush to get into the back

room was so great that three people were forced out a window on the opposite

side and landed in a hospital. The unruliness of her fans prompted Edie Sedgewick

— incredibly gorgeous in a floor-length, shocking pink Rudi Gernreich sheath —

to shriek. Escorted by campus police, the Warhol party swept back to the front

room where they scrambled up a corner stairway. “We want Andy,” the crowd

chanted. ”Well, now I’ve seen Andy Warhol,” one boy crooned, while another

screamed, “Get his clothing!” At the first turn in the stairs, Warhol wheeled

around to look back horror-stricken through his yellow sunglasses. Like the star-crossed

heroines with whom he identifies (Marilyn, Liz, and Jackie), he was menaced by

the disrespectful idolatry of his fans.

The stairway, alas, did not lead

to the second floor, having been boarded up years ago. ”We were trapped like

rats,” Green said, but also protected by four policemen posted at the base of

the stairs. From their perch, Warhol’s party stared at the crowd and the crowd

stared back; both sides seemed to be getting satisfaction. “I wish he would leave

so I could leave,” a boy said. Co-eds pushed forward bearing tins of Campbell’s

pork and beans and Campbell’s tomato soup that were relayed up the stairs for

autographing. An attractive housewife had her book of S & H Green Stamps

autographed; she said she would never redeem them.

Warhol and the Satellites were

rescued by a group of students who cut a hole in the floor above, through which

they made a Beatlesque escape.

Although the show received

unfavorable reviews, Warhol was credited with sparking tremendous in art in

Philadelphia. “All the people thanked me for doing something in Philadelphia ,”

he said.

Massive James Rosenquist Mural Unveiled In Lobby Of 3 World Trade Center The Financial District

BY: SEBASTIAN MORRIS

A James Rosenquist mural titled

Joystick is now on display in the lobby of 3 World Trade Center in the

Financial District. The mural spans 46 feet of the office building’s

ground-floor entryway.

James Rosenquist was born in

Grand Forks, North Dakota and rose to become a seminal figure in the Pop Art

movement of the 1960s. He is most known for his large-scale, collage-style

paintings and major exhibitions at the Guggenheim Museum, Museum of Modern Art,

the Whitney Museum of American Art, and many other institutions both domestic

and abroad. Rosenquist died at his home in New York City on March 31, 2017 at

the age of 83.

As described by James Rosenquist

Studio, Joystick, which was originally painted in 2002, is an ode to

Rosenquist’s love of flying. The abstracted visualization is based on

reflections of various forms from within a central mirrored cylinder moving at

a great speed.

Lily Rosenquist, artist and

daughter of James Rosenquist, oversaw installation of the mural.

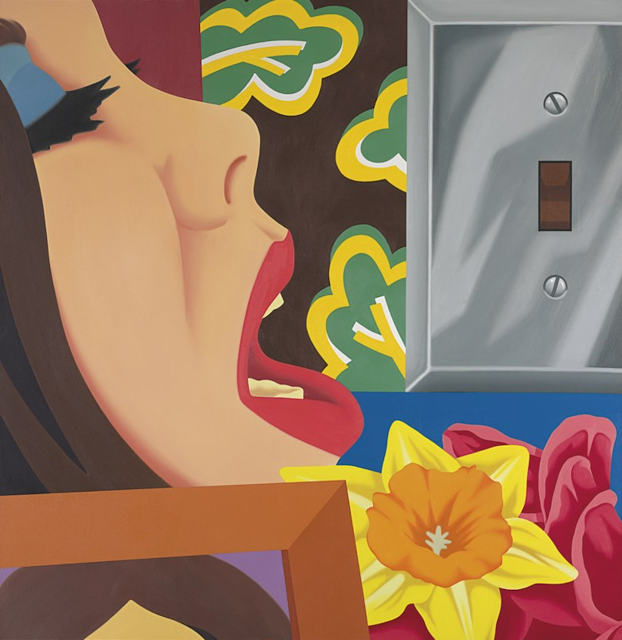

Girl with Tear I by Roy Lichtenstein, 1977

Edited from Wikipedia

Roy Fox Lichtenstein (October 27,

1923 – September 29, 1997) was a pop artist. During the 1960s, along with Andy

Warhol, Jasper Johns, and James Rosenquist among others, he became a leading

figure in the new art movement. His work defined the premise of pop art through

parody.

Inspired by the comic strip, Lichtenstein

produced precise compositions that documented while they parodied, often in a

tongue-in-cheek manner. His work was influenced by popular advertising and the

comic book style. He described pop art as "not 'American' painting but

actually industrial painting".

Whaam! and Drowning Girl are

generally regarded as Lichtenstein's most famous works, with Oh, Jeff...I Love

You, Too...But... arguably third.

His most expensive piece is

Masterpiece, which was sold for $165 million in January 2017

Lichtenstein was born in New

York, into an upper-middle-class Jewish family. He attended New York's Dwight School, graduating

from there in 1940. Lichtenstein first became interested in art and design as a

hobby, through school. He was an avid jazz fan, often attending concerts at the

Apollo Theater in Harlem. He frequently drew portraits of the musicians playing

their instruments.

Lichtenstein then left New York

to study at Ohio State University, which offered studio courses and a degree in

fine arts. His studies were interrupted by a three-year stint in the Army

during and after World War II between 1943 and 1946.

He returned to studies in Ohio under the

supervision of one of his teachers, Hoyt L. Sherman, who is widely regarded to

have had a significant impact on his future work

Lichtenstein entered the graduate

program at Ohio State and was hired as an art instructor, a post he held on and

off for the next ten years. In 1949 Lichtenstein received a Master of Fine Arts

degree from Ohio State University.

In 1951, Lichtenstein had his

first solo exhibition at the Carlebach Gallery in New York.

He moved to Cleveland in the same

year, where he remained for six years, although he frequently traveled back to

New York. During this time he undertook jobs as varied as a draftsman to a

window decorator in between periods of painting. His work at this time

fluctuated between Cubism and Expressionism.

In 1957, he moved back to upstate

New York and began teaching again. It was at this time that he adopted the

Abstract Expressionism style, being a late convert to this style of painting.

Lichtenstein began teaching in upstate New

York at the State University of New York at Oswego in 1958. About this time, he

began to incorporate hidden images of cartoon characters such as Mickey Mouse

and Bugs Bunny into his abstract works.

In 1960, he started teaching at

Rutgers University where he was heavily influenced by Allan Kaprow, who was

also a teacher at the university. This environment helped reignite his interest

in Proto-pop imagery.

In 1961, Lichtenstein began his

first pop paintings using cartoon images and techniques derived from the

appearance of commercial printing. This phase would continue to 1965 and

included the use of advertising imagery suggesting consumerism and homemaking.

In 1961, Leo Castelli started

displaying Lichtenstein's work at his gallery in New York. Lichtenstein had his

first one-man show at the Castelli gallery in 1962; the entire collection was

bought by influential collectors before the show even opened.

A group of paintings produced

between 1961 and 1962 focused on solitary household objects such as sneakers,

hot dogs, and golf balls. In September 1963 he took a leave of absence from his

teaching position at Douglass College at Rutgers.

His works were inspired by comics

featuring war and romantic stories “At that time,” Lichtenstein later

recounted, “I was interested in anything I could use as a subject that was

emotionally strong – usually love, war, or something that was highly charged

and emotional subject matter to be opposite to the removed and deliberate

painting techniques".

It was at this time that

Lichtenstein began to find fame not just in America but worldwide. He moved

back to New York to be at the center of the art scene and resigned from Rutgers

University in 1964 to concentrate on his painting.[26] Lichtenstein used oil

and Magna (early acrylic) paint in his best known works, such as Drowning Girl

(1963), which was appropriated from the lead story in DC Comics' Secret Hearts

No. 83. (Drowning Girl now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, New York.)

Drowning Girl also features thick outlines,

bold colors and Ben-Day dots, as if created by photographic reproduction. Of

his own work Lichtenstein would say that the Abstract Expressionists "put

things down on the canvas and responded to what they had done, to the color

positions and sizes. My style looks completely different, but the nature of

putting down lines pretty much is the same; mine just don't come out looking

calligraphic, like Pollock's or Kline's."

Rather than attempt to reproduce

his subjects, Lichtenstein's work tackled the way in which the mass media

portrays them. He would never take himself too seriously, however, saying:

"I think my work is different from comic strips – but I wouldn't call it

transformation; I don't think that whatever is meant by it is important to

art."

When Lichtenstein's work was first exhibited,

many art critics of the time challenged its originality. His work was harshly

criticized as vulgar and empty. The title of a Life magazine article in 1964

asked, "Is He the Worst Artist in the U.S.?"

Lichtenstein responded to such

claims by offering responses such as the following: "The closer my work is

to the original, the more threatening and critical the content. However, my

work is entirely transformed in that my purpose and perception are entirely

different. I think my paintings are critically transformed, but it would be

difficult to prove it by any rational line of argument."

He discussed experiencing this

heavy criticism in an interview with April Bernard and Mimi Thompson in 1986.

Suggesting that it was at times difficult to be criticized, Lichtenstein said,

"I don't doubt when I'm actually painting, it's the criticism that makes

you wonder, it does."

Lichtenstein began experimenting

with sculpture around 1964, demonstrating a knack for the form that was at odds

with the insistent flatness of his paintings. For Head of Girl (1964), and Head

with Red Shadow (1965), he collaborated with a ceramicist who sculpted the form

of the head out of clay. Lichtenstein then applied a glaze to create the same

sort of graphic motifs that he used in his paintings; the application of black

lines and Ben-Day dots to three-dimensional objects resulted in a flattening of

the form

Most of Lichtenstein's best-known

works are relatively close, but not exact, copies of comic book panels, a

subject he largely abandoned in 1965, though he would occasionally incorporate

comics into his work in different ways in later decades.

Lichtenstein's works based on

enlarged panels from comic books engendered a widespread debate about their

merits as art. Lichtenstein himself admitted, "I am nominally copying, but

I am really restating the copied thing in other terms. In doing that, the

original acquires a totally different texture. It isn't thick or thin

brushstrokes, it's dots and flat colors and unyielding lines."

Although Lichtenstein's

comic-based work gained some acceptance, concerns are still expressed by

critics who say Lichtenstein did not credit, pay any royalties to, or seek

permission from the original artists or copyright holders.

In an interview for a BBC Four

documentary in 2013, Alastair Sooke asked the comic book artist Dave Gibbons if

he considered Lichtenstein a plagiarist. Gibbons replied: "I would say

'copycat'. In music for instance, you can't just whistle somebody else's tune

or perform somebody else's tune, no matter how badly, without somehow crediting

and giving payment to the original artist. That's to say, this is 'WHAAM! by

Roy Lichtenstein, after Irv Novick'."

In the early 1960s, Lichtenstein

reproduced masterpieces by Cézanne, Mondrian and Picasso before embarking on

the Brushstrokes series in 1965. Lichtenstein continued to revisit this theme

later in his career with works such as Bedroom at Arles that derived from

Vincent van Gogh's Bedroom in Arles.

In 1970, Lichtenstein was

commissioned by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (within its Art and

Technology program developed between 1967 and 1971) to make a film. With the

help of Universal Film Studios, the artist conceived of, and produced, Three

Landscapes, a film of marine landscapes, directly related to a series of

collages with landscape themes he created between 1964 and 1966.[53] Although

Lichtenstein had planned on producing 15 short films, the three-screen

installation – made with New York-based independent filmmaker Joel Freedman –

turned out to be the artist's only venture into the medium.

Also in 1970, Lichtenstein

purchased a former carriage house in Southampton, Long Island, built a studio on

the property, and spent the rest of the 1970s in relative seclusion.

In the 1970s and 1980s, his style

began to loosen and he expanded on what he had done before. Lichtenstein began

a series of Mirrors paintings in 1969. By 1970, while continuing on the Mirrors

series, he started work on the subject of entablatures. The Entablatures

consisted of a first series of paintings from 1971 to 1972, followed by a

second series in 1974–76, and the publication of a series of relief prints in

1976.[56] He produced a series of "Artists’

Studios" which incorporated elements of his previous work. A notable

example being Artist's Studio, Look Mickey (1973, Walker Art Center,

Minneapolis) which incorporates five other previous works, fitted into the

scene.

During a trip to Los Angeles in

1978, Lichtenstein was fascinated by lawyer Robert Rifkind's collection of

German Expressionist prints and illustrated books. He began to produce works

that borrowed stylistic elements found in Expressionist paintings. The White Tree

(1980) evokes lyric Der Blaue Reiter landscapes, while Dr. Waldmann (1980)

recalls Otto Dix's Dr. Mayer-Hermann (1926). Small colored-pencil drawings were

used as templates for woodcuts, a medium favored by Emil Nolde and Max

Pechstein, as well as Dix and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Also in the late 1970s,

Lichtenstein's style was replaced with more surreal works such as Pow Wow

(1979, Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Aachen).

Lichtenstein died of pneumonia in

1997 at New York University Medical Center, where he had been hospitalized for

several weeks

Roy Lichtenstein sales records

Work Date Price Source

Big Painting No. 6 November 1970 $75,000

Torpedo...Los! 7 November 1989 $5.5M

Kiss II 1990 $6.0M

Happy Tears November 2002 $7.1M

In the Car 2005 $16.2M

Ohhh...Alright... November 2010 $42.6M

I Can See the Whole Room...and

There's Nobody in It! November

2011 $43.0M

Sleeping Girl 9 May 2012 $44.8M

Woman with Flowered Hat 15 May 2013 $56.1M

Nurse 9 November 2015 $95.4M

Masterpiece January 2017 $165M

A collector's dream: Artwork gifted to OSU Museum of Art on display to help enhance art education

Artwork gifted to OSU Museum of

Art on display to help enhance art education

By Tanner Holubar CNHI News

Oklahoma

George R. Kravis II was a

lifelong fan of art and began collecting at a young age. When he passed away in

2018, he donated more than 700 works of art from his collection to the Oklahoma

State University Museum of Art.

Kravis grew up in an art loving

family, with as much art adorning the home as possible. The family even gave

each other works of art as gifts, which helped spurn a lifelong love of art and

all different types of artwork.

The OSU Museum of Art opened its

latest exhibition this week, titled “In the Mind of the Collector,” which

features a selection of 82 works of art from the collection of Kravis. He was a

strong proponent of art education, which is a main feature of this exhibit.

“A lot of what she’s chosen for

these exhibitions, there’s so many opportunities for our education to do

programming,” said Kristen Duncan, marketing and communications specialist for

the OSU Museum of Art. “For programming with the community, with families, and

for anyone and everyone to come and do activities. The great thing is, this

exhibition will be open through July, but there’s going to be different things

that happen throughout the spring. So we’re hoping we can really engage with

the community with the different events that will be going on.”

One part of the exhibit delves

into how Kravis became an avid art collector, and one piece on display is a

record changer, which he purchased when he was about 10 years old. Kravis

became involved in radio broadcasting, beginning at a station with the call

sign KRAV, and later began collecting radios from the 1930s to the 1950s, with

a number of radios on display as part of the exhibit.

Kravis also developed an interest

in art that referenced pop culture. A couch is on display at the OSU Museum of

Art that is made to represent Marilyn Monroe’s lips. Other pieces were

influenced by comic book artwork, as well as works of art developed by working

architects.

Arlette Klaric, associate chief

curator and curator of collections for the museum, said the OSU Museum of Art

is the only museum in Oklahoma that is focusing on modern and contemporary art.

She said a focus of this exhibit is to showcase objects that are not only

practical use objects, but ones that also serve as artwork.

“This is the first time we’ve had

a design collection,” Klaric said. “One of the goals of the show and the

project, is just to make people more aware of these objects, not only for their

purpose, but for the way they look and for the associations they can have.”

Klaric said with Kravis having

been such a backer of art education, the ability for the OSU Museum of Art to

try to help educate people about art through his collection has helped create a

legacy for the museum.

“It’s amazing. We as a university

art museum, our primary purpose is to teach,” Klaric said. “Our audiences also

teach in their own way and learn. So he’s given us some really important

examples of artwork to share with the community. We got more than 700 objects …

and it’s huge. Collections like this don’t come along every day, and especially

because we’re only five years old, it’s really helping us create an identity.

“And he’s really created a legacy

for the museum with this work. Because it’s a permanent collection, people can

come in and make friends with works of art. It’s just an enormous gift to have

gotten, and I’m in awe of people who do things like this, because this was a

lifetime pursuit for him.”

The goal of this current exhibit

is to help educate people in the community about art through multiple different

events, which will take place during the 2nd Saturdays with a variety of

activities. The first will take place Feb. 8, where people who attend will be

able to take part in the 3D Chair Design Challenge.

Patrons will be able to use the

museum’s 3D printing pens to try and design and build a miniature chair. The

challenge is to see whose chairs will actually be able to stand. The chairs

that will actually stand will be put on display in the museum. The pens used

are non-heating, which makes them safe and fun to use for kids, as well as

anyone who wishes to try the challenge.

Another community activity that

is planned is what the museum dubbed “Cherished Possessions.” People can bring

cherished objects to be photographed, and the object can be special to the

person for a variety of reasons. It could be an object of tremendous

sentimental value, or can be an object that people are proud to own. The

project will be a Polaroid photo taken of the person holding the item, and the

collection of Polaroids will be put on display in the museum’s mini-vault.

It is a project that will evolve

over the course of the exhibit being open, as more and more people’s photos

will be on display, it will grow to be more impactful, as the stories of people’s

objects will create an interesting collage of personal objects from the

community. People who attend the opening reception for the exhibit on Jan. 31

can bring an object and be a part of this artistic endeavor.

Other 2nd Saturday events that

are planned are “Radio Days” on April 11, where people can come for a day of

music and art inspired by pop culture. On May 9 for “Pop Art Day,” people can

come and create art inspired by commodities and pop culture.

Klaric said a special thing about

the OSU Museum of Art is that it provides the people of Stillwater with a

chance to visit an art museum without having to drive into the city to do so.

“For Stillwater, we certainly

have the art department gallery, and now we have this,” Klaric said. “For

people who are interested or who get interested in art, they don’t have to go

60-something miles to Oklahoma City or Tulsa … they can find it right here.

It’s really an important source for the university. It’s one thing to read

about the exhibition, but when you come in and see the objects, it’s a

different experience.”

The OSU Museum of Art is located

at 720 S. Husband St., and is free and open to the public. For more information

on the museum or this exhibit, visit museum.okstate.edu.

At 87, This Icelandic Pop Artist Is Still Making Eye-Popping Work

Alina Cohen

Jan 10, 2020

For over six decades, the

Icelandic artist Erró has made paintings that forgo gentle

aesthetics in favor of riotous visual assaults. His canvases feature

overlapping, appropriated, painted images from everyday sources including comic

books, advertisements, and the media. A representative work, Baby Rockefeller

(1962–63), is a triptych brimming with pictures: grapes, flowers, a butterfly,

Santa Claus, a stork carrying a child in its beak, a Native American warrior, a

dog with a sign that says “Happy Birthday,” a revolver, and a covered wagon.

And that’s just a fraction of it.

Years before the internet

saturated our lives with more information than we could possibly absorb, Erró

was bombarding his viewers with such amalgamations of kitschy figures,

cartoons, and political references. Working in Paris, he espoused the mid-20th

century

Pop

movement that swept across Britain and the

United States. He befriended major figures of the New York art world and helped

break down the barrier between high and low culture.

“Erró represents the nomadic

spirit of how Pop images related to consumption and consumerism were collected

and transposed across the globe,” says Erica Battle, associate curator of

contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA). In 2016, the PMA

mounted “International Pop,” a survey of Pop Art (organized by the Walker Art

Center, where it was shown the year prior), that included Erró’s Foodscape

(1964). The canvas is an overcrowded visual feast made up of cheese plates,

cakes, canned goods, and candy wrappers.

Over the past few years, Galerie

Perrotin has helped raise the artist’s profile among Manhattanites. A new show

opening on January 14th gathers the artist’s collages on paper, spanning the

1950s through 2019. They’re relatively tame works, which offer a

quieter—perhaps more salable—side of the artist’s exuberant practice. Martin

Bremond, associate director at Perrotin, believes the collages make Erró an

“approachable artist, easy to understand and discover.”

Erró was born Gudmundur

Gudmundsson in Iceland, in 1932, to a single mother; he enjoyed a happy, if

unconventional childhood for the time. He once recalled growing up in the

bucolic countryside, “on a farm where you could ride a whole day on a horse and

still be on the same farm.” Early creative skills and dedication led to his admittance

at the Oslo Academy of Fine Art in 1952. He worked in a figurative mode,

painting blocky nudes and Inuits with kayaks.

Marc Chagall

visited and praised one of Erró’s anatomy

studies.

Throughout the early and

mid-1950s, Erró further defined himself as a unique, leading artist. He entered

a brief apprenticeship at Ravenna Mosaic School in 1955, where he made a mark

for himself. He changed his name to the more easily pronounceable “Ferró,”

after staying in the Spanish village Castel del Ferro. He eventually dropped

the “F.”

Throughout the late 1950s, Erró

painted battling, cartoonish skeletons and received an illustrating commission

from Spartacus publishing house. He married an Israeli artist, Myriam

Bat-Yousef, and settled in Paris. Erró was a master networker. His friend, poet

and painter Jean-Jacques Lebel, introduced him to the Parisian Surrealists.

Painter Roberto Matta

visited Erró’s studio, and Erró vacationed at

Irish painter Philip Martin’s Formentera home. All the while, he pushed his own

practice into ghostly new realms, creating haunting, apocalyptic scenes of

monsters merging with machines. Despite this dark material, European and New

York galleries began showing the work. In 1961, Manhattan’s March Gallery

exhibited Erró’s pieces alongside those of Yayoi Kusama and

Allan Kaprow.

Yet Erró didn’t visit New York

until two years later. The extended trip proved pivotal. He met American art

luminaries including

Jim Dine, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom

Wesselmann, Andy Warhol,

Claes Oldenburg, Carolee Schneemann

(with whom he had an affair), Robert Rauschenberg, and James Rosenquist

. Inspired by the country’s

conspicuous consumerism, Erró began scavenging supermarket aisles and city

streets, gathering products, magazines, and postcards. His new paintings, which

reveled in excess, quickly followed. In 1964, New York’s tastemaking Gertrude

Stein Gallery gave the artist his first one-man show in the U.S.

Over the decades, perhaps the

most conspicuous shifts in Erró’s practice regard his source materials. Bremond

notes that throughout the 1970s, Erró incorporated ideas about the Cold War

into his work. Eastern and Western figures appear together, in strange

juxtapositions. The New York Office (1976), for example, depicts former Chinese

Communist leader Mao Zedong sitting in a New York skyscraper, while other works

feature a poster of former Chilean president Salvador Allende, a swastika, or a

likeness of Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara. The Soviet satirical

publication, Krokodil, eventually became one of his favorite sources.

Throughout the 1980s, more pop culture icons appeared. Batman, Superman, and

Wonder Woman reside amid machines and political figures.

Since the 1990s, Erró has

continued to fill his canvases with icons of culture and advertising, such as

cars, Disney figures, and crop tops. In a recent paper collage, the recycling

sign—three arrows curving towards each other into a triangular shape—appears.

Environmental concerns surface, if only at a superficial level.

Erró’s work, according to Bremond,

doesn’t explicitly suggest a political agenda. Instead, he says, “Erró just

wants people to question politics.”

The artist himself, however, had

a different view. “Political paintings and speaking about politics was not

welcome in New York,” he recently explained over the phone, from his Paris

studio. He notes that he no longer solely relies on his own devices for source

material. While he buys American and Japanese comics from a local bookstore,

people also send him images to use.

At 87 years old, Erró is still

looking forward. “The future of art is street art,” he said. It’s easy to see

the vibrant hues, pop culture references, and rejection of formal aesthetic

principles that unite the artist’s work with what one might find along the

walls of Bushwick, Wynwood, or Saint-Denis. Erró is friendly with Parisian

street artist

Speedy Graphito

, whose own cartoon-inflected

designs suggest the elder painter’s influence.

Whether Erró’s work is any “good”

is beside the point. “His Pop-style work is shamelessly derivative, technically

facile, illustrative in the most obvious and superficial ways and completely

without sensuous physical appeal,” Ken Johnson wrote in a New York Times review

of Erró’s 2004 Grey Art Gallery retrospective. And yet, he countered, “despite

your better judgment,” you may find yourself engaged in the artist’s “manic

graphic activity, antic humor, and promiscuous sampling.” So it goes with the

fever dream that is our 24-hour news cycle. It’s difficult to look; it’s even

harder to look away.

MY WRITERS SITE: Are we looking at the actual Mona Lisa?

MY WRITERS SITE: Are we looking at the actual Mona Lisa?: On August 21, 1911, an Italian citizen named Vincenzo Peruggia (October 8,1881 – October 8, 1925) a professional thief, stole the Mon...

Artist Peter Max allegedly siphoned over $4M from elderly relative

By Kathianne Boniello

Famed pop artist Peter Max and

his wife Mary — who committed suicide in June — allegedly siphoned $4.6 million

in cash from their dementia-riddled relative, “Cousin Lou,” according to court

papers.

They used much of the cash to

splurge on bling, including a Cartier bracelet, earrings and a ring

collectively worth $1.485 million; $1.3 million in jewelry from Bhagat; a

Verdura ring costing $58,500; and $47,000 Van Cleef & Arpels earrings,

among dozens of other pricey purchases, according to Lou’s daughter, who is

seeking to recoup the cash.

Ricki Reisner said her dad, Louis

Gottlieb, was so ill in the years before his January 2015 death at age 90 he

didn’t realize the Maxes were taking advantage of him — sometimes writing more

than one hefty check to them a day, she says in a Manhattan Supreme Court

claim.

Gottlieb ran a successful

construction business before moving into money management, carefully investing

the bulk of his cash in bonds for years.

More than 70 pieces of Mary Max’s

jewelry went up for auction Dec. 13, bringing in nearly $1 million, claims

Reisner, who wants a judge to stop Mary Max’s executor, her brother Daniel

Balkin, and Doyle Galleries, which ran the auction, from distributing the

proceeds.

Max was long accused of

mistreating the now 82-year-old Peter, who suffers from Alzheimer’s. Peter Max

previously promised to return the funds in a recorded phone call, according to

court papers.

Peter Max rose to fame during the

“pop art” era of the 1950s and 1960s, using bright colors and a psychedelic

flair before going on to paint for commercial enterprises like the Super Bowl,

cereal boxes and the US Open.

Years before her tragic end,

Peter and Mary Max were allegedly taking trips to see Peter’s “Cousin Lou” on

Long Island — a successful businessman who established a trust worth more than

$11 million for his daughter.

The Maxes got Gottlieb to write

them more than 30 checks in less than two years, Reisner charges.

Mary Max appeared to regard

Gottlieb as nothing more than a piggy bank, salivating over a $250,000 Cartier

ring in an email to a friend and noting the hefty price tag “would be one trip

to Lou if only he weren’t in such a decline,” and leaving “detailed

instructions” for Peter “on how to ask Louis for the money,” according to

Manhattan Supreme Court papers.

Balkin declined comment. Reisner

wants a judge to freeze the auction proceeds.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)