Munich Gets a Crash Course in Pop Art

Munich — Not since Hitler laid the cornerstone of the

House of German Art in 1933 has Munich been known as much of a trailblazer on

the international art scene. In 1993, however, Christoph Vitali took over the

establishment, now called simply Haus der Kunst, and brought with him new

vitality. Mr. Vitali had already put one exhibition space on the map,

Frankfurt's Schirn Kunsthalle. Thanks to his expertise and connections, Munich

now hosts a caliber of traveling show that used to bypass southern Germany in

favor of Cologne, Hamburg or Berlin.

The best expression of the new wind blowing through the

city is the current blast of pop art. For the Haus der Kunst, Mr. Vitali

managed to get a piece of the Roy Lichtenstein action, a Munich stop (through

Jan. 8) on the grand tour of the retrospective that opened at the Guggenheim in

1993. He's even added a number of works that weren't shown in New York.

Following suit is another museum with another recently arrived director: The

Villa Stuck, headed since 1992 by Jo-Anne Birnie-Dansker, currently hosts the

Tom Wesselmann retrospective (through Jan. 15) traveling around Europe until

the end of 1996.

For Munich to have two major shows of this nature at once

is unprecedented. That they happen to coincide enables audiences here to take

what amounts to an in-depth crash course in this

Though Mr. Lichtenstein is seven years older than Mr.

Wesselmann, each artist arrived at his characteristic idiom around 1961. In

Munich, the works that weren’t shown in New York include Lichtensteins from the

1950s in which the artist searches, with increasingly wandering brush strokes,

for a certainty he finds only when he hits upon existing cultural icons.

There’s a new strength and energy to, for instance, a 1958 ink sketch of Donald

Duck. We see that Mr. Lichtenstein has found his voice: not an image, but a

full vocabulary of representation.

This language is, above all, two-dimensional. But an

idiom that the public imagination tends to reduce to an image of comic-book

rapture is really an attempt to show how conventions of representation affect

all our perceptions. Using his print screens and dots to filter both the world

and the art-historical past, Mr. Lichtenstein looks at the way the modern eye

flattens Picasso, Mondrian, Cezanne into mere reproductions — symbols that are

the coin of a devalued cultural currency. This is one of the central themes of

pop art: Warhol, too, pointed to the way that the “Mona Lisa” or “The Last

Supper” has ceased to be a painting and has instead become an icon for a large

segment of the public.

To put him in a conventional art-historical slot, Mr.

Lichtenstein is a narrative painter, but his comic-book scenes are fragments of

stories to which there is no beginning and no end. This hardly matters: The

moments he selects are representative, not even so much of the shallow characters

as of the society that has produced them. These works also invoke a convention

of narration that reduces a story to its superficial, surface elements.

But eventually surface concerns take over altogether.

When Mr. Lichtenstein began painting empty mirrors in the early ’70s, he

brushed content and subject right out of the picture. The paintings of the next

two decades show him struggling to find a way back in. He returns to allusions,

citing everyone from the surrealists to — in a period of particular yearning

for solidity — de Kooning; he falls back on the time-honored device of the

artist's studio, which lets him quote from himself. The limitations of surface

are best expressed in the series of “Imperfect Paintings” from the late ’80s —

the rectangular picture plane is no longer able to sustain the compositions,

which have to be supported on irregular

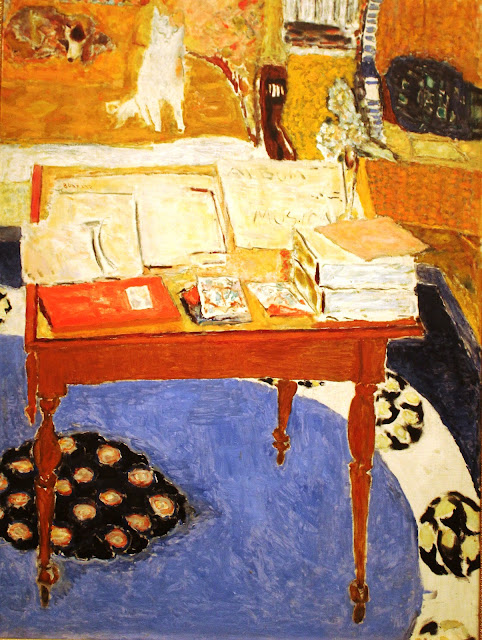

Mr. Wesselmann is a much happier artist than is Mr.

Lichtenstein, and more fluent in his medium. Evident throughout his oeuvre is

his delight in the physicality of paint, metal, plastic. Like Mr. Lichtenstein,

Mr. Wesselmann focuses on surface, but his surfaces are above all tactile,

sensuous. The nexus of themes central to this work is sexuality, at once

voluptuous and sanitized, the “safer sex” of advertising images. Mr.

Wesselmann's platform is the billboard; instead of narratives, he paints still

lifes and landscapes, nudes and altarpieces to the American Dream.

Surface also functions as a screen for the viewer’s own

projections of that dream. The earliest “Great American Nudes” are flat,

featureless, even amorphous pink shapes lounging on draperies of Matissean

brilliance -- their surfaces gradually develop into the desirable but equally

anonymous gleaming curve of a car body, a breast. From the mid-’80s on, the

white space surrounding the nudes becomes the ground on which Mr. Wesselmann

inscribes sketches of brightly enameled metal: pretty, colorful, facile images

of nudes, still lifes. The images are tasteful and marketable; indeed, they've

been on sale at two Munich galleries since 1992.

As his works scale down, Mr. Wesselmann steps up his

quotations: “Monica Sitting With Mondrian“ or “Nude With Cezanne,” even

“Bedroom Face With Lichtenstein.” Like Mr. Lichtenstein years before, Mr.

Wesselmann is making a statement about the way famous images are reduced to

reproductions, or, here, to background.

But in the end, Messrs. Wesselmann’s and Lichtenstein’s

works are just as vulnerable as are any of the Old Masters to the process of

being reduced to reproduction — more so, in fact, because pop images are

already executed in the vocabulary of reproduction. And time has dulled the

force of their message. These pretty pictures no longer stir up their audience,

no longer pose a threat to lazy viewing habits. The works of Messrs. Wesselmann

and Lichtenstein have become commodities, repossessed by the idiom of

reproduction and mass-production — T-shirts, wall calendars and mugs — about

which these two artists were originally making a statement.

Museum of Modern Art to host Martha Rosler’s ‘Meta-Monumental Garage Sale’

That's the theory behind Martha Rosler's

"Meta-Monumental Garage Sale," a large-scale version of the classic

commercial tradition that will, quite literally, be open for business at the

Museum of Modern Art starting Nov. 17.

Rosler will always be at the exhibit, her first solo show

at the museum, to run the sale, according to the museum's press release. Museum

visitors will have the opportunity to haggle for goods donated by the public,

the artist and museum staff - and then take pictures with the items they score.

The artist first became interested in the garage sale

format when she moved from New York to southern California, where the

“phenomenon” was much more prevalent.

"I was struck by the strange nature of these events,

their informal economic status and self-centeredness, but also the way they

implicated the community in the narrative of the residents' lives," Rosler

said in an interview with the exhibit's curator, Sabine Breitwieser, for MoMA's

website.

The second-hand goods up for grabs at MoMA are in flux

since the museum just recently solicited . Records, posters, "good art and

bad art" - and "obsolete science textbooks" are just some of the

knick-knacks the artist requests.

Most of the donations so far have been "easily

portable objects," Breitwieser told Art in America back in March. But

there are some that stand out - namely, a child-size piano.

This is far from Rosler's first garage sale. In fact, you

could say she's quite the regular.

Her first took place in 1973 at a University of

California, San Diego, art gallery — an exhibit she advertised "as a

garage sale in local newspapers and as an art event within the local art

scene."

Rosler told Breitwieser that her first sale was designed

to create a space “where the question of worth and value, use and exchange,

[were] both glaringly placed front and center and completely represented and

denied.”

Since then Rosler has made a name for herself through her

political photomontages, such as her Vietnam War-era series, “Bringing the War

Home."

But "Garage Sale" has continued to go on the

road.

Among other institutions, it was displayed at the New

Museum in 2000 and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Britain in 2005 — and

has accumulated new "merchandise" along the way.

Proceeds from the MoMA sale will go to charity - but

Rosler is keeping mum on exactly which charities they’ll be.

"Martha doesn't want to name them," Breitwieser

told Art in America, "because people shouldn't feel they're giving money

to a particular charity. They're giving to an art project--and they're buying

things!"

How Capitalism Can Save Art

Does art have a future? Performance genres like opera, theater, music and dance are thriving all over the world, but the visual arts have been in slow decline for nearly 40 years. No major figure of profound influence has emerged in painting or sculpture since the waning of Pop Art and the birth of Minimalism in the early 1970s.

Warhol grew up in industrial Pittsburgh. Today's college-bound rarely have direct contact with the manual trades.

Yet work of bold originality and stunning beauty continues to be done in architecture, a frankly commercial field. Outstanding examples are Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Spain, Rem Koolhaas's CCTV headquarters in Beijing and Zaha Hadid's London Aquatic Center for the 2012 Summer Olympics.

What has sapped artistic creativity and innovation in the arts? Two major causes can be identified, one relating to an expansion of form and the other to a contraction of ideology.

Painting was the prestige genre in the fine arts from the Renaissance on. But painting was dethroned by the brash multimedia revolution of the 1960s and '70s. Permanence faded as a goal of art-making.

But there is a larger question: What do contemporary artists have to say, and to whom are they saying it? Unfortunately, too many artists have lost touch with the general audience and have retreated to an airless echo chamber. The art world, like humanities faculties, suffers from a monolithic political orthodoxy—an upper-middle-class liberalism far from the fiery antiestablishment leftism of the 1960s. (I am speaking as a libertarian Democrat who voted for Barack Obama in 2008.)

Today's blasé liberal secularism also departs from the respectful exploration of world religions that characterized the 1960s. Artists can now win attention by imitating once-risky shock gestures of sexual exhibitionism or sacrilege. This trend began over two decades ago with Andres Serrano's "Piss Christ," a photograph of a plastic crucifix in a jar of the artist's urine, and was typified more recently by Cosimo Cavallaro's "My Sweet Lord," a life-size nude statue of the crucified Christ sculpted from chocolate, intended for a street-level gallery window in Manhattan during Holy Week. However, museums and galleries would never tolerate equally satirical treatment of Judaism or Islam.

It's high time for the art world to admit that the avant-garde is dead. It was killed by my hero, Andy Warhol, who incorporated into his art all the gaudy commercial imagery of capitalism (like Campbell's soup cans) that most artists had stubbornly scorned.

The vulnerability of students and faculty alike to factitious theory about the arts is in large part due to the bourgeois drift of the last half century. Our woefully shrunken industrial base means that today's college-bound young people rarely have direct contact any longer with the manual trades, which share skills, methods and materials with artistic workmanship.

Warhol, for example, grew up in industrial Pittsburgh and borrowed the commercial process of silk-screening for his art-making at the Factory, as he called his New York studio. With the shift of manufacturing overseas, an overwhelming number of America's old factory cities and towns have lost businesses and population and are struggling to stave off disrepair. That is certainly true of my birthplace, the once-bustling upstate town of Endicott, N.Y., to which my family immigrated to work in the now-vanished shoe factories. Manual labor was both a norm and an ideal in that era, when tools, machinery and industrial supplies dominated daily life.

For the arts to revive in the U.S., young artists must be rescued from their sanitized middle-class backgrounds. We need a revalorization of the trades that would allow students to enter those fields without social prejudice (which often emanates from parents eager for the false cachet of an Ivy League sticker on the car). Among my students at art schools, for example, have been virtuoso woodworkers who were already earning income as craft furniture-makers. Artists should learn to see themselves as entrepreneurs.

Creativity is in fact flourishing untrammeled in the applied arts, above all industrial design. Over the past 20 years, I have noticed that the most flexible, dynamic, inquisitive minds among my students have been industrial design majors. Industrial designers are bracingly free of ideology and cant. The industrial designer is trained to be a clear-eyed observer of the commercial world—which, like it or not, is modern reality.

Capitalism has its weaknesses. But it is capitalism that ended the stranglehold of the hereditary aristocracies, raised the standard of living for most of the world and enabled the emancipation of women. The routine defamation of capitalism by armchair leftists in academe and the mainstream media has cut young artists and thinkers off from the authentic cultural energies of our time.

Over the past century, industrial design has steadily gained on the fine arts and has now surpassed them in cultural impact. In the age of travel and speed that began just before World War I, machines became smaller and sleeker. Streamlining, developed for race cars, trains, airplanes and ocean liners, was extended in the 1920s to appliances like vacuum cleaners and washing machines. The smooth white towers of electric refrigerators (replacing clunky iceboxes) embodied the elegant new minimalism.

"Form ever follows function," said Louis Sullivan, the visionary Chicago architect who was a forefather of the Bauhaus. That maxim was a rubric for the boom in stylish interior décor, office machines and electronics following World War II: Olivetti typewriters, hi-fi amplifiers, portable transistor radios, space-age TVs, baby-blue Princess telephones. With the digital revolution came miniaturization. The Apple desktop computer bore no resemblance to the gigantic mainframes that once took up whole rooms. Hand-held cellphones became pocket-size.

Young people today are avidly immersed in this hyper-technological environment, where their primary aesthetic experiences are derived from beautifully engineered industrial design. Personalized hand-held devices are their letters, diaries, telephones and newspapers, as well as their round-the-clock conduits for music, videos and movies. But there is no spiritual dimension to an iPhone, as there is to great works of art.

Thus we live in a strange and contradictory culture, where the most talented college students are ideologically indoctrinated with contempt for the economic system that made their freedom, comforts and privileges possible. In the realm of arts and letters, religion is dismissed as reactionary and unhip. The spiritual language even of major abstract artists like Piet Mondrian, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko is ignored or suppressed.

Thus young artists have been betrayed and stunted by their elders before their careers have even begun. Is it any wonder that our fine arts have become a wasteland?

—Ms. Paglia is University Professor of Humanities and Media Studies at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. Her sixth book, "Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art From Egypt to Star Wars," will be published Oct. 16 by Pantheon.

Shopping List: Tuna, Detergent, a Warhol

Shopping

List: Tuna, Detergent, a Warhol

Along with the bales of

toilet paper and drums of tomato sauce that Costco customers load into their

online shopping carts, they can now add an original Warhol or Matisse, a result

of this giant discount retailer’s recent decision to re-enter the fine-art

market.

Quietly and cautiously,

like someone newly divorced returning to dating, Costco has begun selling fine

art again after quitting the business six years ago when questions were raised

about the authenticity of two Picasso drawings it had sold online.

In the two or so weeks

since Costco, a warehouse club store, began listing “Fine Art” in the Home

& Décor section of its Web site, it has sold 8 of the 10 works it initially

listed, including two framed lithographs by Henri Matisse, one for $1,000, and

the other for $800; a framed lithograph by Georges Braque for $1,400; a framed

screen print by Andy Warhol for $1,450; and a framed textile-and-paint collage

by Heather Robinson for $1,699.99, said Greg Moors, the San Francisco dealer

supplying the art to Costco.

Mr. Moors said he has about

five more works that he expects to list on the Web site over the weekend, but

added that it takes time to find and frame original art.

Ginnie M. Roeglin, senior

vice president for e-commerce and publishing at Costco, said, “We just started

this program and are just testing a few things.” She declined to comment

further on the decision to sell art again.

Mr. Moors said in an

interview that he was driven by his vision of art for everybody, and he

dismissed any incongruity in the notion of a discount warehouse club selling

fine art. For many gallery owners and Internet art sellers, “the deal is more

important than the customer,” Mr. Moors said, but with a brand-name store like

Costco, “the customer is more important than the deal.”

Galleries will sometimes

take sizable markups on works of art they purchase for resale, according to

dealers. By contrast, Mr. Moors said, Costco is charging a maximum of 14

percent over what they pay him, the same markup it applies to all its

merchandise.

Costco is certainly not the

first large chain to offer fine art. Between 1962 and 1971, Sears sold more

than 50,000 works by artists like Picasso, Rembrandt, Chagall and Whistler

through its catalog and in its stores as part of the Vincent Price Collection

of Fine Art. Customers at Sears could buy a work on layaway for as little as $5

down and $5 a month. Sears guaranteed every purchase just as it would with a

refrigerator or lawn mower.

Costco also guarantees

“satisfaction on every product we sell, with a full refund” within 90 days of

purchase. Mr. Moors’s phone number is listed under “product details” on the Web

site so that potential buyers can ask him questions.

Costco stopped selling fine

art in 2006 after Picasso’s daughter Maya Widmaier-Picasso questioned the

authenticity of a few drawings attributed to her father that the store was

selling. Those works ranged in price from $37,00 to $146,000 and did not come

from Mr. Moors, who started supplying museum-quality art to Costco in 2003.

This time, the retailer is offering lower-priced items, he said.

Shoppers who now click on

the company’s Web site can find lithographs for three and four figures, less

than many of the televisions Costco regularly sells.

The lithographs are

primarily unsigned. As Mr. Moors explained, unsigned works eliminate the

potential problem of forged signatures.

He said he was taking other

steps to ensure the art’s authenticity. “Certain artists are known to have had

problems,” he said. “For instance, although I like him as an artist, I won’t go

near Dalí.” Mr. Moors was referring to the proliferation of fake Dalí prints on

the market.

Ultimately, the best way to

avoid suspicion, he said, is to work with living artists. At the moment he

plans to offer art by Ms. Robinson and Johnny Botts, another California artist,

who says on his Web site that he uses “simple shapes, hard edges and happy

colors” to make his whimsical robots.

Mr. Moors came across Ms.

Robinson’s work at a boutique and studio space she shares with a jewelry

designer on Mission Street near the Bernal Heights section of San Francisco.

Mr. Moors chose colorful pieces that combined fabric and paint for the Costco

collection, Ms. Robinson said. Her art is being offered on consignment, and the

contract she signed with Mr. Moors does not prevent her from selling her

artwork anywhere else, including her own Web site.

Asked what her initial

reaction had been to to Mr. Moors’s proposal to sell her art at Costco, Ms.

Robinson searched for the right phrase.

“I was a little surprised,”

she started.

“My work is very. ...” she

continued.

“It’s not necessarily. ...

“When you think of Costco.

...”

“How should I put it?” she

asked, before settling on the idea that selling her work at Costco “would not

have occurred to me.”

Nonetheless, she is

thrilled to have access to Costco’s 60 million members. “It’s a really great

way to get exposure for my work in a way I wouldn’t be able to get on my own,”

Ms. Robinson said, adding, “I know their customers are really important to

them, and they have a really loyal following.”

As Mr. Moors said: “She is

starting off with an audience of 60 million people. You can social-network for

the next 30 years and never get that audience.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)